Salt Lake West Side Stories: Post Thirteen

by Brad Westwood

Salt Lake’s west side underwent massive and constant changes during the last quarter of the nineteenth century.

What began as a fort where Mormon pioneers sought shelter, transformed into a transportation, industrial and manufacturing hub, and by the late nineteenth century experienced dramatic social and environmental consequences as a result. For example, in 1894, the county courthouse moved from the area, and the City and County building on Washington Square took its place. Local government’s presence and influences left the neighborhood. New businesses also opened that met the recreational desires of its residents. In 1890 there were 82 taverns or bars in Salt Lake City. By 1907 there were 147 taverns or bars, with many of them located on the west side. Often, local officials tolerated gambling, prostitution, and other “vices” because they received bribes to look the other way.

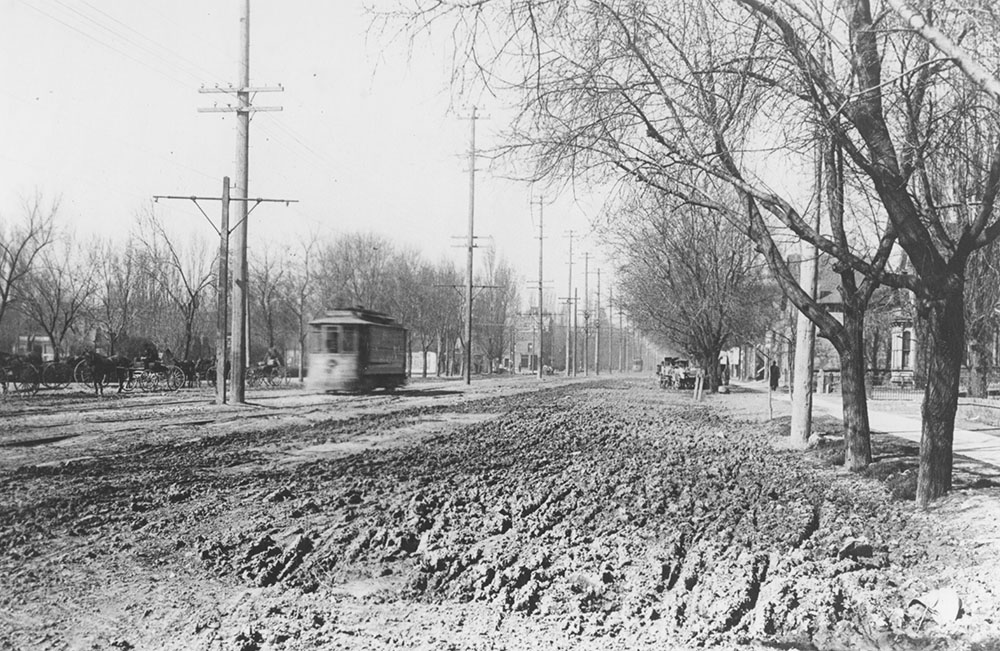

Post-Civil War rapid industrialization also introduced severe environmental consequences to Salt Lake City. As historian Thomas Alexander argues, during the 1890s, Salt Lake City was known as one of the ugliest and dirtiest cities in America. Salt Lake City’s unhealthy living conditions were mainly due to its large number of railroad tracks, which was higher per capita than any other city in the United States. Nationally, Salt Lake City’s low ranking was due to several factors, including terms of miles of water lines per capita, and access to residential plumbing and sewers. The city had one of the highest numbers of unpaved or poorly paved streets in the nation. The lack of public services and infrastructure weighed heavily on late nineteenth century Salt Lake City residents. During the Progressive Era (1880-1920), some members of the “new” middle-class engineered and built municipal infrastructures with the intention of “reforming” city life. Notably, Salt Lake City’s Progressive reforms occurred much later than most other American cities.

“In 1890 there were 82 taverns or bars in Salt Lake City. By 1907 there were 147 taverns or bars, with many of them located on the west side.”

There were also social and cultural changes that took place as new migrants moved into the west side. Many of the chapels, churches, and synagogues who initially found homes on the west side moved outside of the Pioneer Park neighborhood. The Jewish Temple, the Presbyterian Church, the Roman Catholic Church, the African American churches, and the Baptist Church all moved to more affluent areas of the city or suburbs where the majority of their members now lived. In the 1920s, the St. Mary’s Academy changed its name to St. Mary’s of the Wasatch and moved from the west side to the foothills near 1300 South and 2600 East.

While many commercial, government, and religious organizations left Salt Lake City’s west side, some remained and expanded. In 1923 Holy Trinity Cathedral replaced the original Greek Orthodox Church that was located on 400 South and looked down South Rio Grande Street. The new sanctuary was built kitty-corner, north and east, across from Pioneer Park. In the 1970s, the Greek Orthodox community added a large center to serve community members. A new Buddhist Temple replaced the older 1920s building on 100 South Street in Japan Town. The neighborhood remained as a toehold and a beloved long-standing community-base for nearly every immigrant population well into the late twentieth century.

Salt Lake’s west side was constantly in flux as new industries, communities, and organizations moved in and out of the area. In many ways, the area represents what happened to most American cities that underwent dramatic changes during post-Civil War industrialization. Many of these changes included severe economic consequences that affected the people who lived in them.

We hope you join us for our next installment of Salt Lake West Side Stories, where we will talk about how Utahns’ attempted to address public health problems and severe environmental conditions.

Do you want to read the next post (Post 14)? SALT LAKE CITY LOSES ITS “DIRTIEST CITY” STATUS, THE WEST SIDE, PUBLIC HEALTH, AND THE CITY’S ONLY SURVIVING PIONEER SQUARE

Click here to return to the complete list of posts.

Contributors: This post was researched and written by Brad Westwood with a whole lot of help from friends. Thanks to our sound engineer and recording engineer Jason T. Powers, and to his supervisor Lisa Nelson, both at the Utah State Library’s Reading for the Blind program. Thanks also to yours truly, David Toranto, for narrating this post.

Selected Readings:

Benjamin M. Cater, Health, Medicine, and Power in the Salt Lake Valley, Utah, 1869-1945, Ph.D. Dissertation (Salt Lake City: University of Utah, 2012).

Andrew Hurley, Environmental Inequalities: Class, Race, and Industrial Pollution in Gary, Indiana, 1945-1980 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1995).

Stanley S. Postma, P.E. Roger Cisneros, Jim Roberts, Carter & Burgess, Inc., and the Utah Department of Transportation Research Division, “I-15 Corridor, Reconstruction Project, Design/Build Evaluation, 2001 Annual Report.”

Eileen Hallet Stone, A Homeland in the West, Utah Jews Remember (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2001), 3-20.

Do you have a question or comment? Write us at “ask a historian” – askahistorian@utah.gov