Salt Lake West Side Stories: Post Eighteen

by Brad Westwood

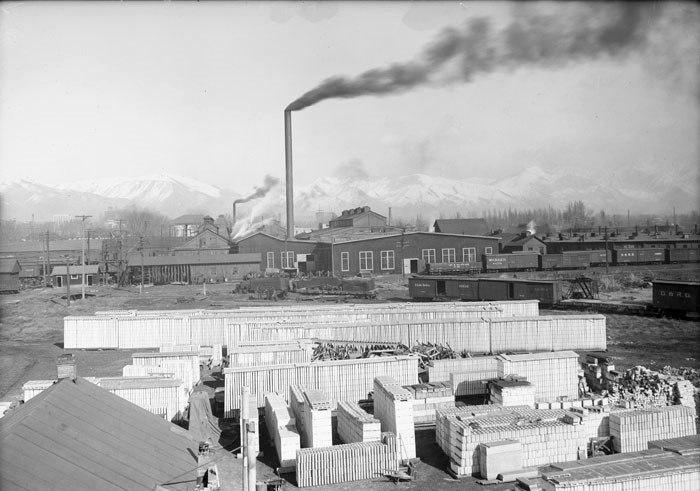

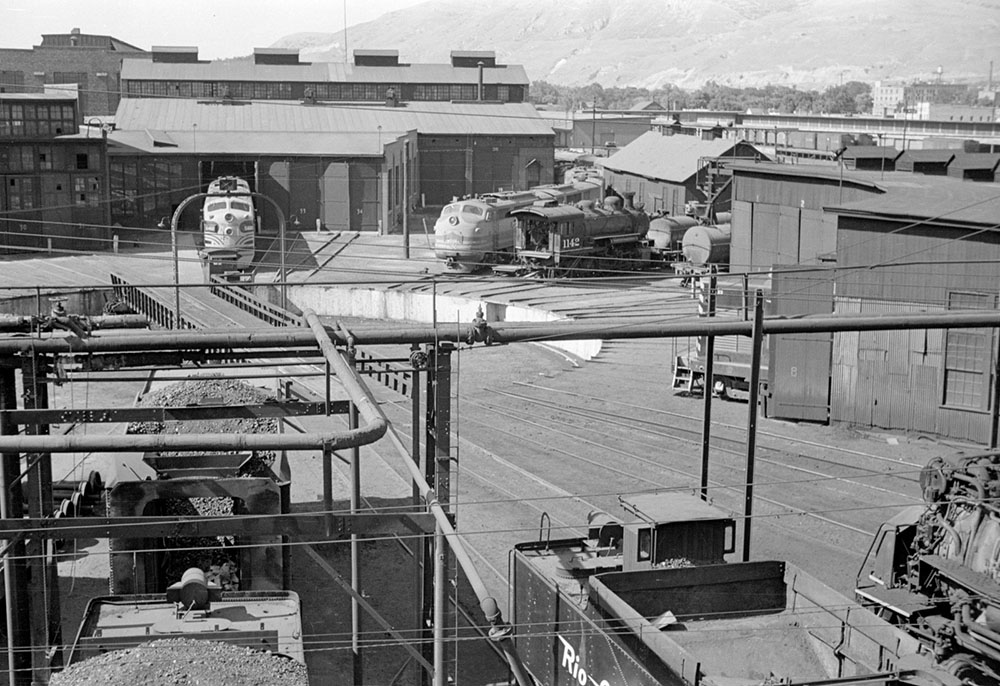

In the decades following the Civil War, the United States emerged as one of the world’s largest economic engines. It was railroading, mining and industry that attracted thousands of economic emigrants to Utah, that allowed Utah to be part of this larger economic story.

The United States’ emergence as an industry leader was due to the mistaken idea that the country had an unlimited supply of natural resources that included water, minerals, ore, and timber. America’s rapid industrial growth was also due to its vast and growing transportation network that included canals, railroads, and roads. The country, including Utah, was able to expand its economic sector because of the ability to attract eastern and international investors. Finally, as the United States continued to industrialize, it relied on less costly labor from around the world that secured its economic might.

As Utah historian John McCormick observed in The Gathering Place: An Illustrated History of Salt Lake City (2000), over 25 million immigrants came to America between 1880 and 1910 to work in America’s labor-intensive industries. In all, roughly 12,000 to 14,000 foreign laborers came to Utah from eastern and southern Europe, Asia, the Ottoman Empire, the Middle East, Mexico, and Latin America to build a new life. Their choice to settle in Utah made Utah’s culture a more vibrant and diverse place. Salt Lake City’s industrial and business history is inseparably linked to the thousands of immigrants who made their mark on Utah’s economic sector.

Immigrants who arrived in Salt Lake City seeking employment were in many ways no different than the Mormon (members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, hereafter the LDS Church) migrants who answered the call to gather in Utah by the LDS Church. Both immigrant groups often settled around people who spoke their language or came from the same region as they did. Non-Mormon immigrants, however, lived predominately in Salt Lake City’s west side, between and around the two railroad depots, or in Utah’s company and industrial towns such as Frisco, Bingham, Midvale, Terrace, and Park City.

Immigrants who settled in Utah usually gathered in different city sections. For instance, during the 1910s and 1920s, Salt Lakers frequently referred to the area between 300 South and 500 West as “Little Syria.” These blocks also included people from Serbia, Croatia, Slovenia, Albania, and Yugoslavia. Migrants from Turkey, Armenia, and Lebanon also settled in the area as they escaped the crumbling Ottoman Empire that was dismantled after World War I. All of the immigrant newcomers lived, worked, and contributed to Salt Lake City and Utah’s growing economy. Today there are many proud communities scattered across the Wasatch Front, and beyond, whose ancestors once lived in one of the many micro-communities located in the Pioneer Park neighborhood.

Mining was one “pull factor” that attracted laborers to Utah. Before the completion of the transcontinental railroad in 1869, Utah had two registered mining districts. A decade later, the territory had over forty, and the number continued to grow throughout the century. Dozens of smaller railroads linked Utah mines, smelters, and processing plants to national and global markets. Utah’s expanding industrial economy exploded due to the combination of mineral extraction and rail lines. Saying this, Utah’s railroad building, mining, smelting, and manufacturing were small when compared to the industrial development that transformed the Mid-Atlantic, the Upper South, and the Midwestern states, which are known today as America’s “Rust Belt.” Even with the Intermountain West’s comparatively small economic expansion, economic opportunities increased nearly tenfold for Utah’s citizens. It also benefited hundreds of national and international investors.

Post-Civil War rapid industrialization continued to transform Utah’s economic and cultural landscape. Of course, the territory was already diverse because of its Native American peoples, and because of the many religious immigrants from Europe and Scandinavia, who heard the call of the LDS Church to gather in Utah. It was, however, Utah’s other pioneers, generally economic immigrants, who played a little-known role in Utah’s quest for statehood. As historian Thomas Alexander explained, between 1870-1890, “with the growth of mining, railroading, and commerce, the composition of the population changed so dramatically that by 1890 Protestants, Catholics, Jews, Orthodox, Buddhist and sundry others, constituted nearly 44% of Utah citizenry” (“Utah’s Constitution: A Reflection of the Territorial Experience,” Utah Historical Quarterly, Vol. 64 No. 3 (summer 1996) p. 264). This percentage would gradually decrease again between the two World Wars; however, at statehood in 1896, along with other well-known factors, it was this shift in Utah’s population which contributed to the United State Congress granting statehood to Utah.

“While the early Mormon pioneers shaped the Intermountain region and made the ‘desert bloom like a rose,’ it was Utah’s gritty, industrial capitalistic economy – its railroading, mining and commercial enterprises of the nineteenth century – that made statehood, and Utah’s modern world, possible.”

Utahns love celebrating the pioneer period (1847-1869), and in a sense it is Utah’s creation story: a struggling religious community forges a path into the wilderness, struggles for survival and thereafter creates a near self-sustaining agriculture-based society, all with implacable cooperative ideals. While the early Mormon pioneers shaped the Intermountain region and made the “desert bloom like a rose,” it was Utah’s gritty, industrial capitalistic economy – its railroading, mining and commercial enterprises of the nineteenth century – that made statehood, and Utah’s modern world, possible.

Agriculture, and a network of Mormon settlements, were not the only endeavors that provided a path to statehood. It was the rise of commercial enterprises along with their demand for laborers that made statehood and Utah’s modern world possible. The influx of non-Mormon immigrants, along with the cessation of polygamy and the LDS Church’s commitment to democracy, altogether made statehood possible in 1896.

The blocks that surrounded Pioneer Park served as a hub for Utah and Salt Lake City’s urban and economic transformation. The many peoples and places in Salt Lake City’s west side served as a wellspring for what eventually became the metropolis we know today.

In our next two installments of Salt Lake West Side Stories, we’ll discuss the impact of labor agents, and the importance of benevolent and mutual aid organizations, to Utah’s immigrant communities.

Do you want to read the next post (Post 19)? BROKERS OF HUMAN CAPITAL

Click here to return to the complete list of posts.

Contributors: This post was researched and written by Brad Westwood with a whole lot of help from friends. Thanks to our sound engineer and recording engineer Jason T. Powers, and to his supervisor Lisa Nelson, both at the Utah State Library’s Reading for the Blind program. Thanks also to yours truly, David Toranto, for narrating this post.

Selected Readings:

Thomas Alexander, “Utah’s Constitution: A Reflection of the Territorial Experience,” Utah Historical Quarterly, 64, 3 (summer 1996): 264-281.

John McCormick, The Gathering Place: An Illustrated History of Salt Lake City (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 2000).

Richard O. Ulibarri, “Utah’s Ethnic Minorities: A Survey,” Utah Historical Quarterly, v. 40, no. 3 Summer (1972): 210-232.

Do you have a question or comment? Write us at “ask a historian” – askahistorian@utah.gov