Words by Wendy Ogata | Photographs by Todd Anderson

Marion Masada had a shocking story to tell about what happened to her as a girl at an Arizona concentration camp during World War II. But she kept it to herself for 12 years, telling it for the first time to a kind man she was dating.

“I never told my parents,” Masada said. “I told Sab because he was very kind, very compassionate and very different from all the other fellows I knew, so I felt safe with him.”

After telling Saburo “Sab” Masada that she was molested at Arizona’s Poston War Relocation Center at the age of 10 by the father of her sister’s friend, and receiving Sab’s sweet and comforting response, she married him.

Now, she’s told her stories of life in the Yuma County Poston War Relocation Center, and her late husband’s story of life in Arkansas’ Rohwer War Relocation Center, hundreds of times, all over the country. “The pain that was in me was coming out, it wasn’t festering in my body,” she said.

“And the more I told it,

Marion Nakamura MasadA

the more I became free.”

Until Sab Masada passed away in 2020, after 64 years of marriage, Marion and her husband had recounted their camp experiences hundreds of times, all over the country — mostly at high schools and universities. She also recorded a three-hour oral history interview with a park ranger from the Manzanar National Historic Site, a concentration camp in California. In addition, a documentary about the Masadas, “Silent Sacrifices,” won an Emmy award in 2019.

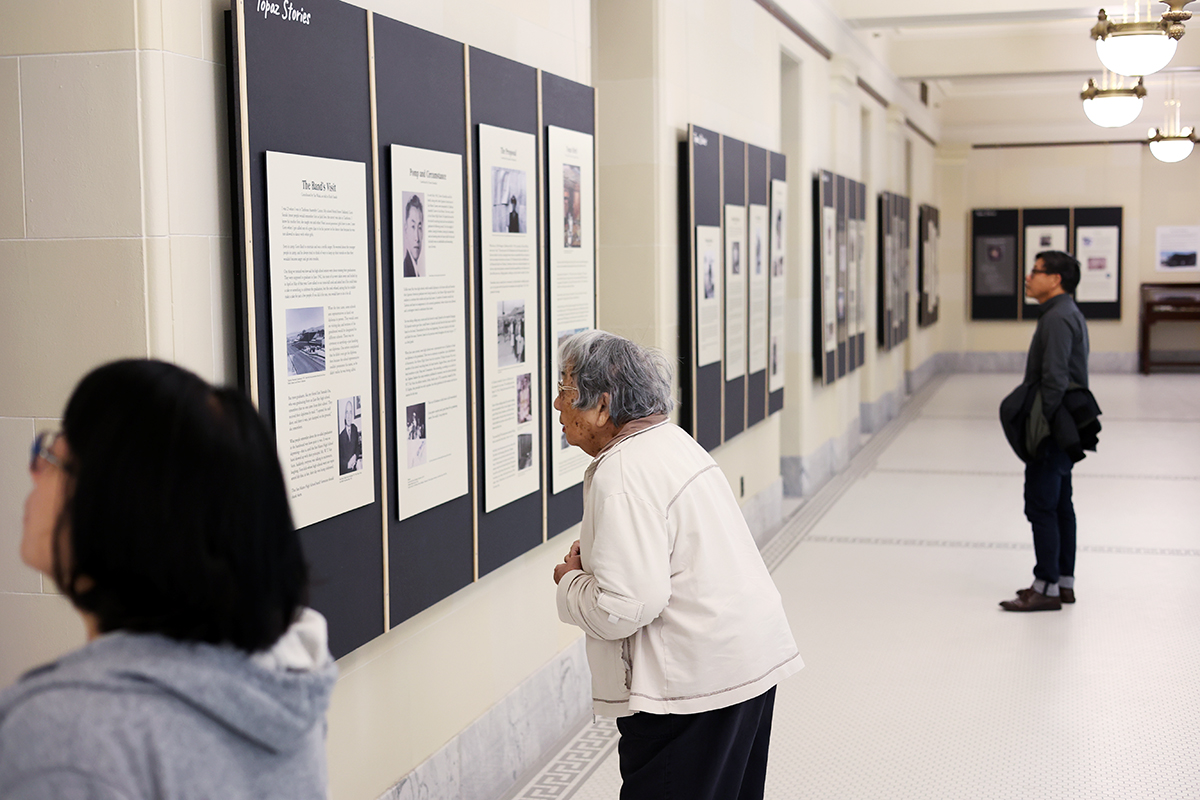

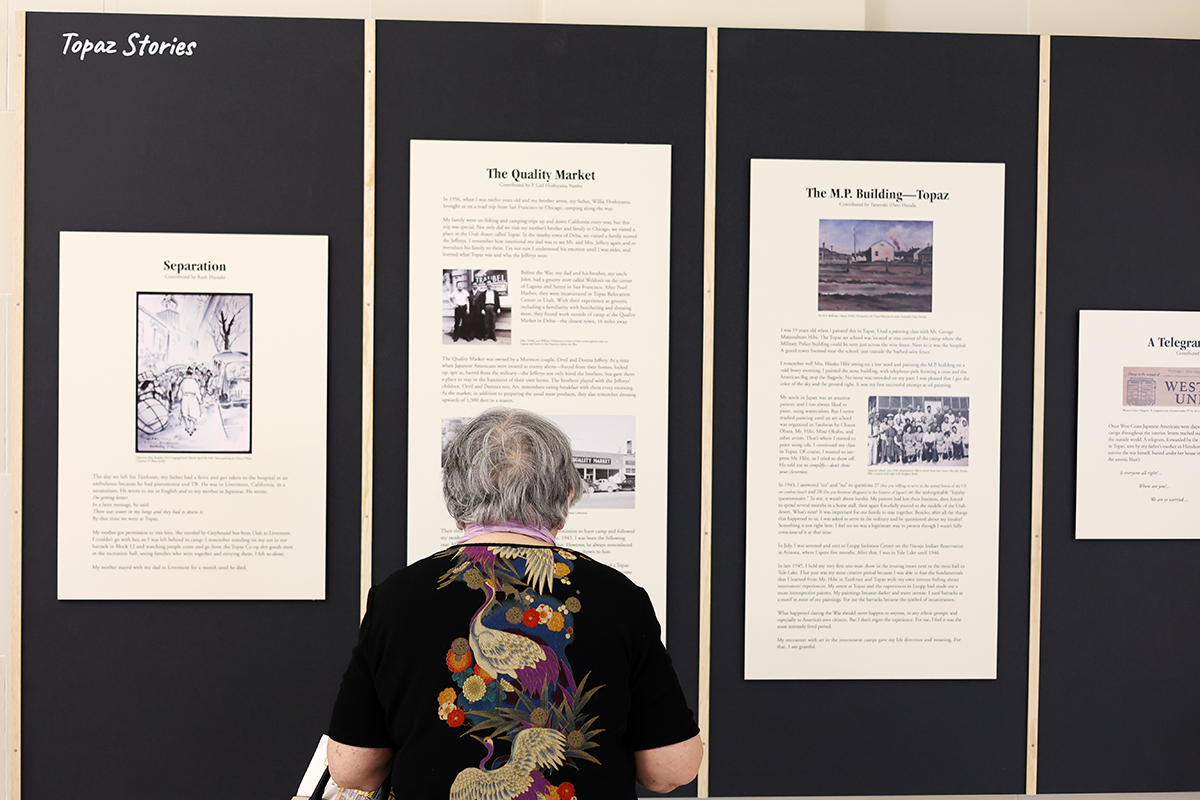

On Monday, Oct. 17, 2022, Masada came to Utah to read other survivors’ stories on display in the “Topaz Stories” exhibit at the Utah State Capitol. Masada’s camp was in a desolate corner of desert near the Arizona/California state line. So she relates to the desert landscape of Topaz, located near Delta in Millard County.

The “Topaz Stories” exhibit includes more than 30 stories paired with photographs and mementoes of the harsh camp life endured from 1942 to 1945 by 11,000 people of Japanese descent, most of them United States citizens. “Personal Justice Denied,” a 1982 report by the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians, concluded there was no military necessity for sending 120,000 West Coast residents of Japanese descent to the 10 camps after Japan bombed Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941. The commission attributed the action to wartime hysteria, racism, and a failure of political leadership.

As a young girl, Marion Nakamura was uprooted from her family’s prosperous farming operation in Salinas, Calif., and sent to Poston wearing all the clothes her mother could fit on her. Their family of eight — Mom, Dad, and six kids ranging from ages 5 to 13 — could take only two bags each to camp, so it made sense to wear as many pieces of clothing as possible. That is, until they stepped off the train in the Arizona desert and its 100-plus-degree temperatures.

Another camp story she tells is heartbreaking. A friend had a 12-year-old mentally handicapped sister. When soldiers came to pick up the family at their home, “the guard said, ‘She can’t go with you,’” Masada said. There was a physical struggle as the family tried to get their daughter in the truck with them. In the end, they were forced by the armed guards to leave her behind. “A month later, they heard she had died.”

Masada said she tells her stories out of a “debt of gratitude” to the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, an all-Japanese unit of the U.S. Army that distinguished itself fighting in Europe during World War II. Many of the 442’s soldiers volunteered to fight for their country while their families were imprisoned behind barbed wire by that same country.

“These young men went to battle and died on our behalf so we could have a good life after the war,” she said. “Many of them died calling out ‘ka-chan’ for their mothers. It just grabs my heart. So, in tribute to them … we’ve got to tell these stories and how their families suffered in the camps.”

Because both her parents worked in the camp, it was young Marion’s job to do the family’s laundry on a washboard. It would take her a full day. “I didn’t get to play much,” she said, but she did get to read. She remembers loving the camp’s Novel Hut, a collection of used books. When she read about Nancy Drew and the Bobbsey Twins, she would be transported beyond the barbed wire to the outside world.

After the camps closed in 1945, Masada said she began working in the homes of “hakujin” (Caucasian) families for 50 cents an hour and would later also board in their homes so her family had one less mouth to feed. When she had weekends off, she would stay with the family of her friend Elsie Frontani Ruffo, a girl she met on her first day at San Jose High School. Elsie’s family, Masada said, treated her with love and generosity and helped her believe again in the goodness of others. “I became part of their family,” she said. “They restored my faith in humanity. They saved my life.”

After Marion married Sab Masada in 1956, he was called to serve as the minister of Ogden’s Japanese Christian Church. They were both young, Marion, 24, and Sab, 27. They served there until 1969, when he was called to Watsonville, Calif., to serve at the Westview Presbyterian Church.

The “Topaz Stories” exhibit is supported by Friends of Topaz and the Topaz Museum, plus numerous state entities including the Utah Department of Cultural & Community Engagement, the Utah Division of Arts & Museums, the Capitol Preservation Board, the Governor’s Office and the Utah House and Senate. It’s on view at the Utah State Capitol through the end of the year.

Editor’s Note: the exhibit “Topaz Stories,” will be leaving the Utah State Capitol at the end of December 2022, and will be reinstalled, to be announced, at the Topaz Museum in Delta, Utah. To read all of the stories, not just those profiled in this exhibit, go to digital exhibit Topaz Stories: Remembering the Japanese American Incarceration in Utah. Finally, if you want to learn more about Utah’s Japanese American internment camp story, visit the museum and its web space @ Topaz Museum.

__________________________

Freelance writer Wendy Ogata worked more than 30 years in journalism, editing and writing at The Salt Lake Tribune, The Ogden Standard-Examiner, and Deseret News, before retiring in 2020. Her extended family includes an uncle who was incarcerated at the Heart Mountain War Relocation Center near Cody, Wyo.