Salt Lake West Side Stories: Post Nine

by Brad Westwood

The completion of the world’s first transcontinental railroad in 1869 dramatically affected the social, political, economic, and cultural life of Salt Lake City (SLC), the Territory of Utah, and the American West.

Transportation was one aspect that contributed to changes in the West. The railroad cut travel time from the Pacific to the East Coast (or vice-versa) from three months down to six to ten days. The railroad also affected cultural identity. In the Utah Territory, the coming of the railroad, for better or for worse, solidified the idea that migrants or immigrants who traveled to Utah before 1869 were the only official “pioneers.” The expansion of the railroad further enlarged and diversified Utah’s economic and social sectors and ushered in a whole different group of pioneer stories.

Native Americans lived in what is now Utah for thousands of years before Mormon (members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints) settlement. After 1847, Utah’s Native Americans did not leave. Instead, they struggled to maintain their sovereignty as colonizers claimed ownership of their lands. Throughout the nineteenth and into the twentieth centuries, migrants and immigrants flocked to Utah for several reasons. Some migrants moved to Utah to participate in the Mormon exodus. Other migrants arrived from around the world hoping to find jobs. The railroad made it possible for members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) and for all other migrants, or immigrants, to choose Utah to settle. Suffice it to say that the railroad was instrumental in bringing change to the Utah Territory. After the Civil War, and the arrival of the Central Pacific and the Union Pacific railroads, America’s industrial revolution arrived in Utah, and the Pioneer Park neighborhood was at the very center of this development.

Mormon interest in the railroad predated the completion of the transcontinental railroad. In 1847, some of the original Mormon migrants to Utah thought about what route would be best for future rail lines as they journeyed to the Great Basin. Forever a pragmatist, Utah’s first territorial Governor and President of the LDS Church, Brigham Young strongly recommended to the United States Congress that Salt Lake City be the meeting place for the transcontinental railroad. On January 31, 1854, he sent a letter to Thomas Kane who lived in Philadelphia, one of the LDS Church’s most ardent eastern friends, to tell him that Salt Lake City was “the natural great Central Depot to Southern California and Oregon” and the “natural diverging point or crossing place.” Essentially, Young believed Utah was the “crossroads of the West.”

Up until 1868, Young and the Utah Territorial Legislature continued to lobby to make the city as the intersection point between the eastern and western United States. That year it became clear however, that the railroad would not meet in Salt Lake City but instead would connect at Promontory Summit, Box Elder County, on the barren edge of the Great Salt Lake. May 10, 1869, the eastern and western lines of the world’s first transcontinental railroad met beyond Salt Lake City. However, by year’s end it was transferred to Ogden soon to become known as “Junction City.”

Members of the American press and some United States congressmen believed, or at least hoped, that the transcontinental railroad would either aid in the demise of or at least dilute the influence of the isolation loving, polygamist practicing Mormons. Brigham Young and the LDS Church’s hierarchy, however, had different plans and a different response to the coming railroad. As historian Brigham D. Madsen explained in his book, Corinne: The Gentile Capital of Utah, nineteenth century Mormons characterized Salt Lake City and its Pioneer Park Neighborhood as a community free from the vices that they believed plagued cities throughout the country (1980, page 3). The ideas about Salt Lake City’s potential are best expressed in a sermon Brigham Young delivered in the Salt Lake Tabernacle and recorded by a stenographer on October 8, 1868. On that day, Brigham Young explained how Mormon society would prepare culturally and particularly economically for the coming of the railroad:

“Our outside friends say they want to civilize us here. What do they mean by civilization? Why they mean by that, to established gambling holes—they are called gambling halls—grog shops and houses of ill fame on every corner of every block in the city; also swearing, drinking, shooting and debauching each other. Then they would send their missionaries here with faces as long as jackasses’ ears, who would go crying and groaning through the streets, ‘Oh what a poor, miserable, sinful world!’ That is what is meant by civilization. That is what priests and deacons want to introduce here; tradesmen want it, lawyers and doctors want it, and all hell wants it! But the Saints do not want it, and we will not have it (Congregation said, Amen!). A true system of civilization will not encourage the existence of every abomination and crime in a community but will lead them to observe the laws Heaven has laid down for the regulation of the life of man. There is no other civilization.”

Brigham Young, “Salvation Temporal and Spiritual—Self-Sustaining—Civilization,” Journal of Discourses, Vol. 12, p. 287, complete sermon pgs. 281-289.

For Young and his cadre of church leaders, the railroad, if managed by a Mormon “civilization,” would aid in the development of an ideal society. Furthermore, if Mormons maintained its leadership, Utah would continue to be free from crime and all kinds of debauchery. Finally, the technological advances that the railroads ushered in would expedite the solidification of Young’s idealized Mormon civilization.

Young wanted Salt Lake City to become a western city upon a hill. What the railroad did unequivocally was to allow for an expansion of mechanical, steam, and hydro-based innovations in the territory. These technologies influenced Utah’s cultural, economic, and social landscapes, especially on the west side. Thousands of migrants and immigrants arrived by train and found work in Utah’s newly industrialized cities and hamlets. In the middle of all of this was the Pioneer Park neighborhood, which was the first and the largest of the many interconnected, industry-related, ethnic enclaves that spread across Utah and the Intermountain West.

“…the arrival of the tracks made the Pioneer Park neighborhood one of Utah’s earliest locations to be considered ‘the other side of the tracks.'”

The arrival of American and international immigrants to Utah also meant dramatic changes to social structure. Many territorial citizens perceived the influx of new migrants as “strangers,” while overlooking the fact that they, themselves, were also recent arrivals to the area. A history of the Salt Lake City Police Department explains that territorial citizens concluded that the “tracks” brought a “new wave of strangers.” These strangers, the history continues, did not take kindly to the previously existing “blue laws” or statutes that prohibited illegal entertainments. This included dancing and drinking after curfew and on Sundays. Early police records highlight that the new arrivals made “concerted efforts” to “eliminate such laws” hoping to alter cultural expectations to align with their not-so-Mormon lifestyles.

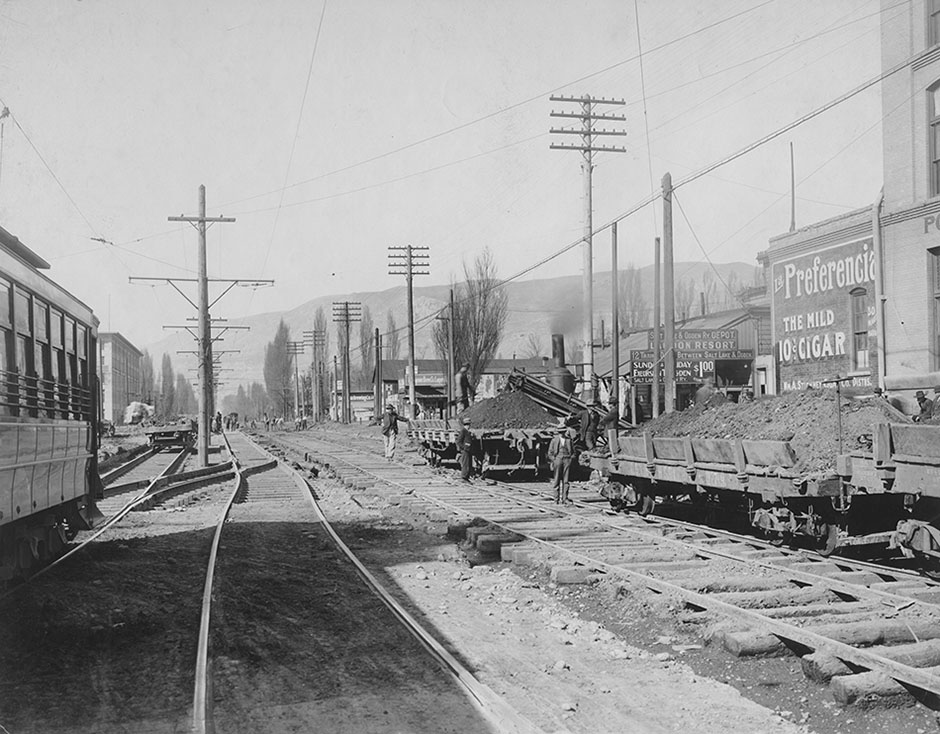

The expansion of railroad lines also created clear divisions between different parts of the city and the rest of the Salt Lake valley. The tracks literally divided the city and the county – as it would also do in Ogden and Weber County. In fact, the arrival of the tracks made the Pioneer Park neighborhood one of Utah’s earliest locations to be labeled as “the other side of the tracks.” Mormons had initially designed the west side, along with every other section of the city, as residential with rural-like blocks consisting of livery stables, sheds, gardens, and orchards. After the railroad arrived, residential and agricultural lots shared the land with railroad yards, railroad associated industries and railroad benefiting businesses.

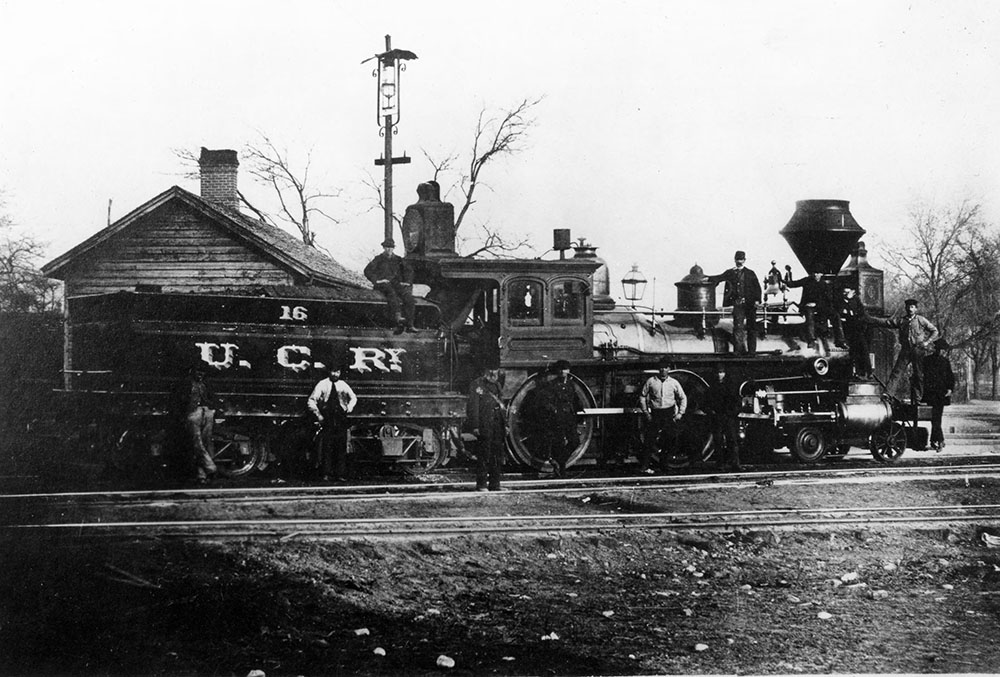

Railroad tracks continued to expand through Salt Lake Valley well into the early twentieth century. The first came in 1871 and 1872, when the Utah Southern Railway (an extension of the Utah Central Railway) extended the Utah Central Railway tracks south, creating a transportation corridor that connected Weber, Salt Lake, Utah and Juab counties to the nation’s larger transportation network. Initially this LDS Church-controlled railway ran alongside miles and miles of homes, agricultural outbuildings, and farms.

Railroads also expanded Utah’s economic sector as well. The mining industry was an endeavor that prospered with railroads. Railroads made mining and smelting economically viable. Historian Brigham Madsen explained that “railroad workers and other Gentiles began to have visions of opening the rich mines of Utah, now that there were means of transportation for ores to the smelters and markets of the east” (Madsen, p. 2). The railroad opened the Great Basin and Utah’s economy to the profits derived from mining that was largely funded by eastern and international investors.

During the 1870s and 1880s, other railroad companies, including the Oregon Short Line and the Denver & Rio Grande Western, built direct connections to and from Salt Lake City. These companies also purchased land in the Pioneer Park neighborhood for their depots, railroad yards and maintenance centers. They constructed massive roundhouses, machine shops, engine and railroad car building facilities. Railroad-related industries and benefiting businesses expanded constantly in the west side. From the 1890s, and into the first two decades of the 1900s, the Western Pacific Railroad, the Salt Lake & Los Angeles Railway (known first as Saltair Railway and later the Salt Lake, Garfield & Western Railway), the San Pedro, and the Los Angeles & Salt Lake Railroad, a subsidiary of Union Pacific, also expanded the industrial footprint of Salt Lake City’s west side.

Along with the larger regional and in-state railroad carriers, the west side also became the hub and the key passenger destination for Utah’s two major interurban railroads (earlier versions of the UTA Frontrunner). Before and during the early years of America’s explosive automobile culture, many Wasatch Front residents used interurban rail service. The Salt Lake & Ogden Railway arrived first. Notably, the Salt Lake & Ogden Railway was renamed the Bamberger Electric Railroad (1891-1950s) or “the Bamberger.” The Salt Lake & Utah Railroad (1914–1946), or the “Orem Line,” followed, running as far south as Payson in Utah County. Both railroad companies built separate passenger depots on the west side. During the early 1920s, the two companies oversaw the construction of a larger combined depot located kitty-corner from the Salt Lake Temple. This Salt Lake Interurban Station was located at about 123 West South Temple, where the Abravanel Hall and portions of the Salt Palace Convention Center now sit.

The railroad industry peaked in Utah between World War I and World War II. In its heyday the railroad companies’ tracks followed or intersected with half of the streets on the west side. The later expansion included lines that ran from the Roper Yard at 2100 South to the Union Pacific yard located at 800 North. The most massive yard in the city was located five to eight blocks west of State Street and had a corridor over one hundred yards wide. Scattered spurs, or secondary tracks, that linked businesses to the main railroad lines, and wyes, or triangular junctions, used for turning around railroad cars, all snaked through the west side neighborhood.

The railroad was not the only means of transportation in Salt Lake City. Horses, wagons, trucks, and automobiles consistently crossed the tracks. As rail lines expanded through the city, other forms of transportation were expected to wait at railroad crossings. The rail yards also proved to be dangerous. From 1911 to 1912, the Union Pacific and Denver & Rio Grande Western constructed concrete and steel viaducts over their rail yards to mitigate wait times. Later they, and eventually the city and the state, built a succession of larger and larger replacement bridges. By the mid-twentieth century, the Interstate-15 (I-15) Freeway with its on and off ramps and exchanges were built in tandem with the prior transportation corridor. It was the rail support systems and allied industries that made the west side different from the rest of Salt Lake City.

Although railroads expanded in Salt Lake, Ogden remained Utah’s national railroad “hub city.” By the turn of the twentieth century, the widest railroad corridor in both cities ran three-quarters to half a mile wide. In Salt Lake City, the Union Pacific and the Denver & Rio Grande Western’s lands covered over one hundred and sixty acres, roughly sixteen ten-acre blocks, and nearly all of it west of the city’s center. Ogden’s railroad yards and its adjacent 25th Street neighborhood have much in common with Salt Lake City’s west side; so much so they should be considered sister communities.

The railroad brought significant changes to Utah by introducing new economic opportunities and thousands of migrants and immigrants to the area. We hope you will join us for our next installment in Salt Lake West Side Stories where we will continue to discuss the city’s industrial transformation. We will also consider the history of Utah’s earliest women’s movements including women’s suffrage, and the building and operating of the LDS Church’s first Relief Society Hall.

Do you want to read the next post (Post 10)? SALT LAKE AS AN EARLY INDUSTRIAL CITY AND THE BEGINNING OF THE RELIEF SOCIETY HALLS

Click here to return to the complete list of posts.

Related Activities: To recognize the enduring impact on Utah of the world’s first transcontinental railroad and the subsequent building of the Utah Central Railway, we recommend that you visit and read the Daughters of Utah Pioneers #358 monument, located in a planter in front of the Union Pacific Depot (east side of The Gateway, 400 West and South Temple). This modest plaque does little justice regarding the massive transformation the railroad had on Utah. We urge that you also examine the railroad’s early twentieth century footprint by studying the U.S. Geological Survey’s topographical map of Salt Lake City and Vicinity, Utah, 1934 from the University of Utah Marriott Library Map Collection, offered by the Seven Canyons Trust website.

Contributors: Special thanks to railroad historian Don Strack, who reviewed all railroad references in this post, including information about equipment and the locations of roads and depots. Special thanks also goes to the Spike150 organization and the Utah Legislature, who, together, supported and funded over a hundred exhibits, lectures, celebrations and programs about Utah and the transcontinental railroad.

This post was researched and written by Brad Westwood with a whole lot of help from friends. Thanks to our sound engineer and recording engineer Jason T. Powers, and to his supervisor Lisa Nelson, both at the Utah State Library’s Reading for the Blind program. Thanks also to yours truly, David Toranto, for narrating this post.

Selected Works:

Brigham D. Madsen, Corinne: The Gentile Capital of Utah (Salt Lake City: Utah State Historical Society, 1980), 2-3.

Lieutenant Michael Ross, ed., “Our History, Serving with Integrity since 1851” from “History of the Salt Lake City Police Department” Salt Lake City, Utah, Police Department.

Ronald W. Walker, Wayward Saints: The Social and Religious Protests of the Godbeites Against Brigham Young (Provo and Salt Lake City: Brigham Young University Press and University of Utah Press, 2009), 128-169.

Brigham Young, “Salvation Temporal and Spiritual—Self-Sustaining—Civilization,” Journal of Discourses by President Brigham Young, His Two Counsellors, the Twelve Apostles, and Others. Reported by G. D. Watt, et al., Liverpool, England: Latter-day Saints’ Book Depot, v. 12, 281-289.

Letter, Brigham Young to Thomas L. Kane, January 31, 1854, Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Vault MSS 792, series 3 subseries 7, subseries 1, item 4, box 15, folder 2.

Do you have a question or comment? Write us at “ask a historian” – [email protected]