By Wendy Ogata | Photographs by Todd Anderson

It took decades for Yae Wada to finally heal her righteous indignation. “I was bitter and I was angry, for many, many years,” she said.

Wada was one of 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry — most of them American citizens — imprisoned behind barbed wire and armed guards after Japan bombed Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941. The Topaz War Relocation Center near Delta held 11,000 people, including Wada.

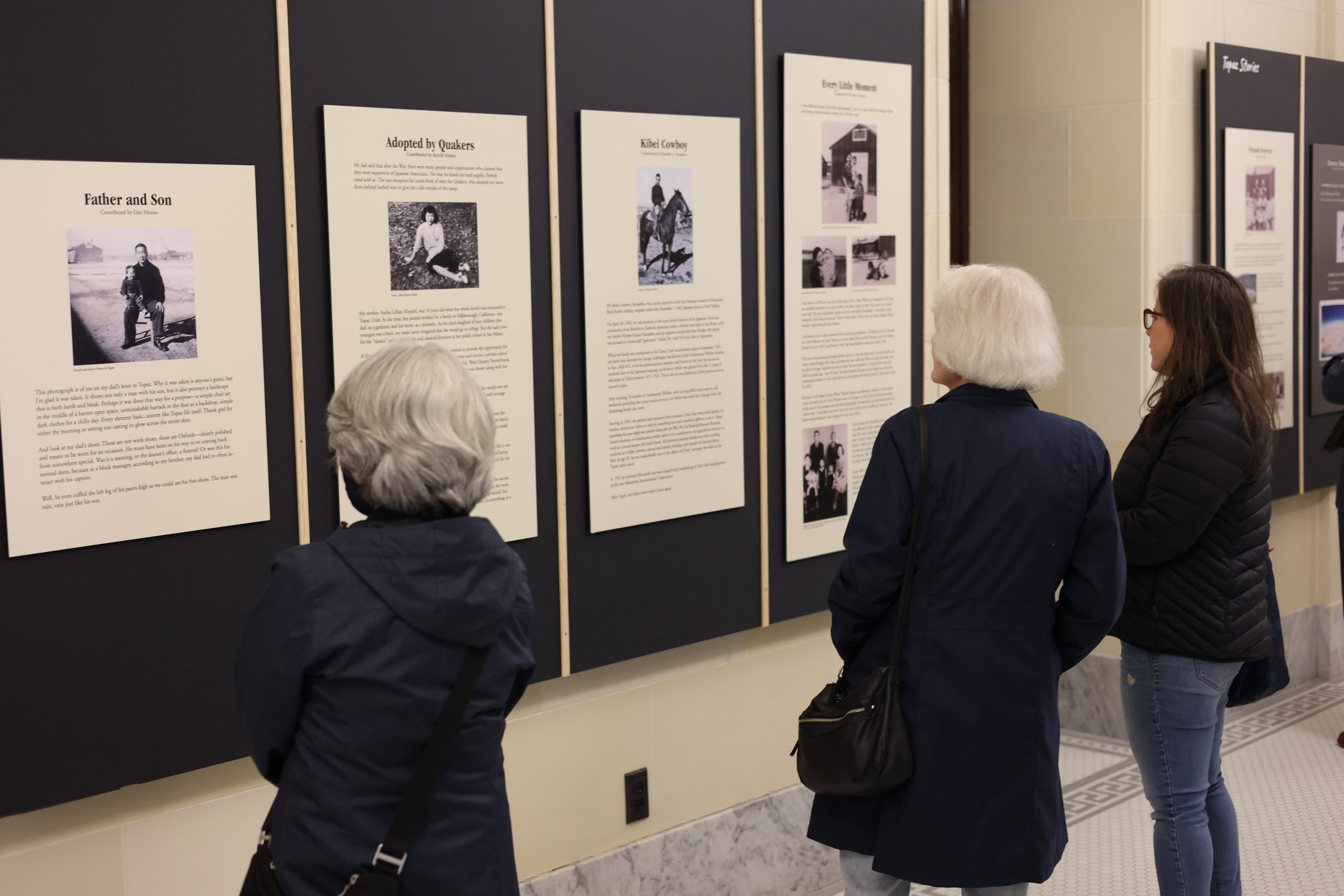

The Topaz Stories” exhibition, at the Utah Capitol in 2022, told these stories of incarceration. Topaz survivors and their families say these stories are more timely than ever, amid rising racist rhetoric and violence against minorities.

“When I hear chants of ‘Send her back!’ I am reminded that the forces of fear and hate are still with us, and the shadow of Topaz looms over us all,” said camp survivor Joseph Nishimura at an April 22 reception for the exhibition. “Topaz Stories” will be on display on the Capitol’s third-floor mezzanine through Dec. 31.

Although told in many voices, the “Topaz Stories” exhibition actually tells just one story — a story of an almost incomprehensible American injustice.

The more than 30 remembrances are from those who were imprisoned by presidential order at the Topaz War Relocation Center. The dusty camp near Delta was one of 10 that detained people of Japanese ancestry after Japan bombed Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941. Topaz held 11,000 people, mostly from the San Francisco area, from 1942 to 1945.

“Topaz Stories” records complicated topics, such as how does a person prove loyalty to their adopted country, as well as simpler ones, such as the tears of a small boy saying goodbye to his dog who cannot go with him to “camp.”

The stark black background on which each story in the exhibit is mounted, plus the raw pine borders, evoke the hundreds of spartan tar paper and wood barracks at Topaz. “That was my intention,” said designer Jonathan Hirabayashi. He was born in American Fork in 1946 after his parents were allowed to leave Topaz to work on a turkey farm there.

The exhibit includes a display of more than 20 artifacts from the camp, including a Boy Scout patch for the Topaz District Council; wooden geta, traditional Japanese footwear that helped keep the wearer out of the Topaz mud; and decorative jewelry made from tiny shells collected near the camp.

Ruth Sasaki, the editor of “Topaz Stories,” said the survivors’ remembrances are more important than ever, given contemporary incidents of injustice and violence against minorities.

It can happen again. I think they are happening again.”

Ruth Sasaki

A reception in April 2022 drew state and community leaders and several camp survivors, most of them in their 80s and 90s. Wada, at 102, is the matriarch of the survivor group.

In an interview, Wada said she lost her business and her home when forced to go to camp, and she was bitter and angry for years.

But in 1988, 43 years after the camps closed, President Ronald Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Act to compensate internees and — more importantly to many — apologize for what happened. The apology letter she received, Wada said, helped heal her anger.

Wada said she is grateful to Utah and in particular the people of Delta, the town nearest Topaz. “They really did everything they could to help us.” One family in particular, she said, was kind to her husband when he would make regular trips to their store in Delta to pick up supplies as part of his job at the camp hospital. She hopes to someday find the family and thank them.

Joseph Nishimura was 8 years old when he and his family were forced from their home in Berkley, Calif., and detained at the Tanforan Racetrack starting in May 1942. Months later they were sent to Topaz. Because he was a child, Nishimura said he had happy memories of camp. “As a kid, you find your own fun,” he said. “We had a good time. I think that was a key characteristic of the experience. Everybody was just trying to make the best of the situation.”

As devout Christians, he said his parents’ attitude was “it’s God’s will or the Lord will provide.”

But a pervasive Japanese cultural attitude also helped the family get through. “My mother was always [saying] ‘Shikata ga nai,’” Nishimura said. While it loses something in translation, the phrase largely means there’s nothing to be done so we just have to live with it.

Nishimura read his Topaz story as one of three shared during Friday’s ceremony. His story ends with him, his mother, and brother leaving Topaz in 1945 and being kicked off a train because of their race.

“That was our first inkling that, although we had left Topaz, it would be with us for a long time to come,” Nishimura said.

“The shadow of Topaz looms over us all.”

Joseph Nishimura

Jeanie Takagi Kashima was the first baby born at Topaz. The camp opened Sept. 11, 1942, and she was born there 11 days later, on the floor of the camp laundry room. She doesn’t remember much about camp. But her mother, she said in an interview, had largely good memories of Topaz.

Many families were separated in the camps, with the men assigned to more secure prisons elsewhere because of their status as community leaders. “I think for her, it was not as sad because the whole family was there. My father was there. She had her father there. Her children were there,” Kashima said of her mother. “She had an intact family so, in a funny way, it was a good time for her.”

The “Topaz Stories” exhibit is supported by Friends of Topaz and the Topaz Museum, plus numerous state entities, including the Utah Department of Cultural & Community Engagement, the Utah Division of Arts & Museums, the Capitol Preservation Board, the Governor’s Office and the Utah House and Senate.

At the reception, Utah Senate President Stuart Adams commented on the diversity of the crowd, praising Utahns for their tolerance and respect for all peoples. “We do more together in Utah than we ever do apart,” Adams said.

Mike Mower, senior advisor of community outreach and intergovernmental affairs in the Governor’s Office, and Sophia DiCaro, executive director of the Governor’s Office of Planning and Budget, presented a proclamation by Gov. Spencer Cox honoring the “Topaz Stories” exhibition. The proclamation called the imprisonment of Americans of Japanese ancestry “one of our state’s and nation’s worst violations of civil rights against American citizens.”

Utah Sen. Jani Iwamoto noted the unanimous passage earlier in the year of Senate Bill 58, establishing Feb. 19 as an annual Day of Remembrance to mark the incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II. Like Sasaki and Nishimura, she said the stories of the exhibition are still vital today, given the “resurgence of hate.”

“It is important to have these conversations, to be visible, honor cultural and economic contributions, become educated, and stand against acts of hate, and stand with each other in solidarity — and to share our stories,” Iwamoto said.

All the stories in the “Topaz Stories” exhibition, plus another 40 not on display, can be read here.

A “Speak Your Piece” podcast about the exhibit, including in-depth interviews of Sasaki and Hirabayashi by Brad Westwood, senior public historian with the Utah Department of Cultural & Community Engagement, is available here. For more information, or to donate to the nonprofit Topaz Museum, click here.

___________________________________

Freelance writer Wendy Ogata is a retired journalist. She worked more than 30 years in journalism, mostly at daily newspapers along Utah’s Wasatch Front. Her extended family includes an uncle who was incarcerated at the Heart Mountain War Relocation Center near Cody, Wyo.