Salt Lake West Side Stories: Post Ten

by Brad Westwood

Not long after the members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (hereafter LDS Church, also known as Mormons) entered the Salt Lake Valley, Brigham Young and members of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles instructed Henry G. Sherwood and Orson Pratt, to design an ideal agrarian-based city.

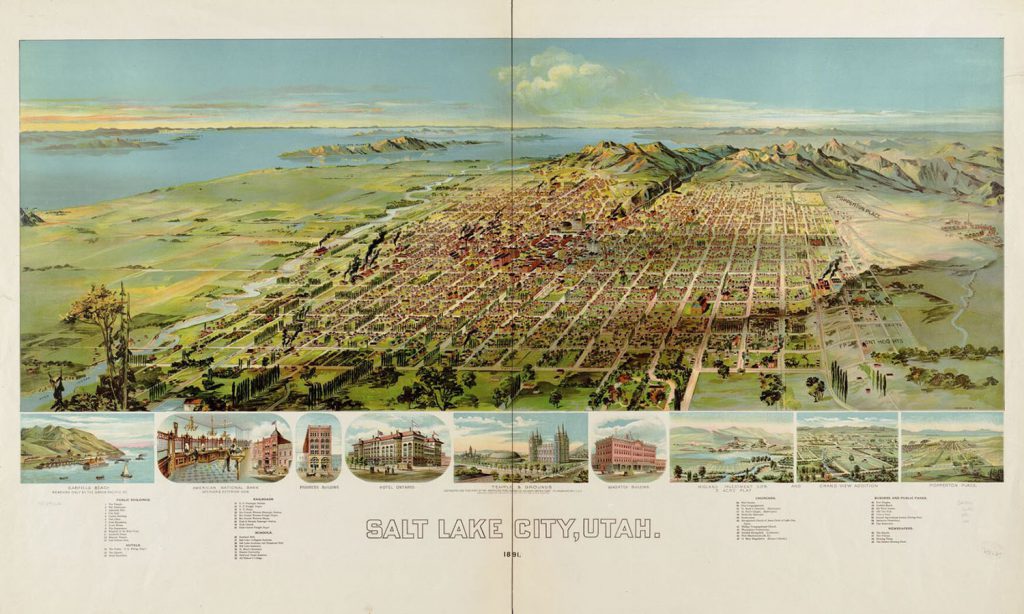

Young’s ultimate goal was to create a city comprised of farmers, with the hope of resisting the avarice and vices that frequently beset city life. The agrarian-based design would enable residents’ access to land, water, air, and light. Despite his best intentions, the arrival of the railroad, along with commercial interests and job seeking immigrants, transformed Young’s original design into a booming industrial urban center. In addition, all of this was aided by the Women’s movement.

Young first articulated his design for the future city when he announced the location of the Salt Lake Temple in 1847. He called for a town organized on a one square mile grid with a temple square in the center and four parks, one in each quadrant. The plan consisted of ten-acre blocks divided into eight lots, with 132-foot-wide streets, running east to west and north to south. Homes were to stand back from the road surrounded by outbuildings, shade trees, gardens, and orchards. He also worked to avoid placing homes directly across the street from one another. Brigham Young’s goal, besides designing an agrarian city, was to create “uniformity throughout the City” (Scott Kenney, Wilford Woodruff’s Journals, 3:239). He also believed that his design would resist density by offering farmers large five- to ten-acre lots just south of the city. Despite his design, the location’s rough terrain, the declared location of the temple, and Young’s desire to control the water flow out of City Creek, foiled some of the key elements in Young’s first uttered plan. The general vision however, for an agrarian city, was carried out.

The intent of President Young and the Quorum of the Twelve was to build an open, semi-agricultural “city” essentially in the wilderness. Mountain-fed streams and rivers would provide irrigation water to all residential and farm lots. He and other church leaders initially resisted the creation of a commercial district in Salt Lake City by encouraging resident-based home industries and selling. Church leaders urged members to perform tasks such as shoemaking, cloth production, wagon building, iron mongering and tin smithing, tanning, carpentry, and more as home businesses.

Comprehensive city planning and zoning beyond these early city plans did not come until the 1920s when lawmakers adopted comprehensive zoning laws. Between the original agrarian city and its constant mixed-use growth, and all the post-Civil War industrialization that followed the railroads, the city was a hodgepodge of land uses. Never was this mixed-use more evident and more perplexing than in the west side neighborhood.

Many Mormon residents gradually moved from the west side, as more non-Mormon immigrants and larger industries moved into the area. The history of the Sixth Ward (448 South and 400 West) reflects this. As the ward became more industrialized and more ethnically diverse, it lost many of its Mormon residents. In 1922, the ward merged with the Seventh Ward, to become the Sixth-Seventh Ward. Then, in 1949, taking in an expanded geographical area, the ward was reorganized again even as it retained the Sixth-Seventh Ward name.

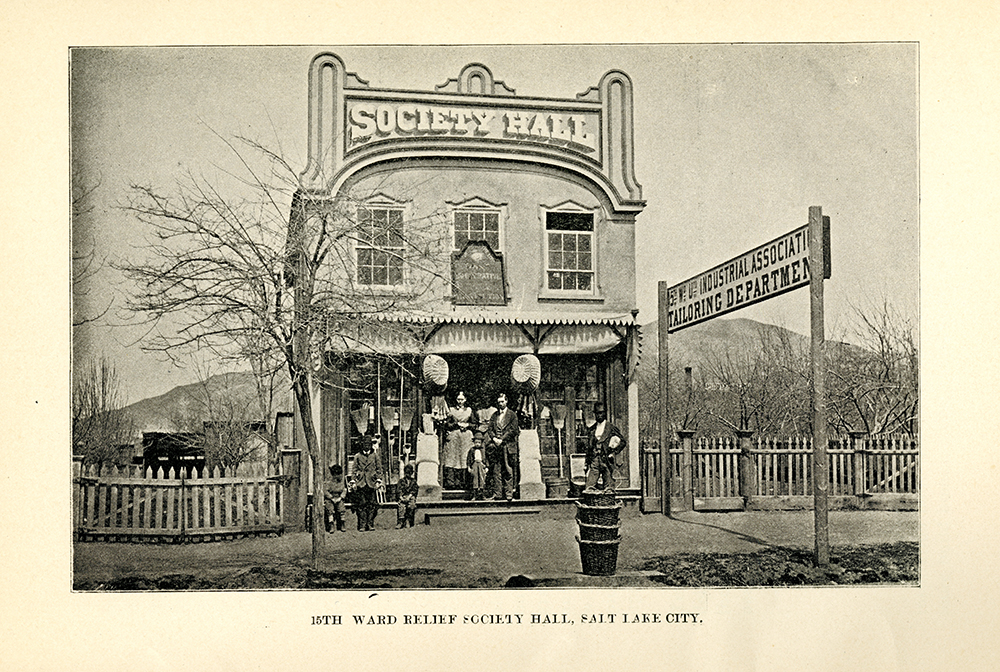

The arrival of the railroad introduced many unwanted economic and social influences. In response to the coming railroad, Mormon women were asked to assist the church in making and selling goods that were previously offered by the city’s expanding merchant class (Mormon and non-Mormon alike). In response, the LDS Church’s Fifteenth Ward’s women’s organization, or “Relief Society,” built what became the Fifteenth Ward Relief Society Store and Hall at 340 West and 100 South. Brigham Young had originally disbanded the Relief Society in 1844 only to reestablish the women-based organization again in 1868. Prior to its second official recognition, the Relief Society functioned in small independent groups throughout Salt Lake City. The Fifteenth Ward Store and Hall once stood where the Delta Center (previously the Vivint Center, 301 West South Temple) is now located. The store offered dry and home manufactured goods, foodstuffs, fine tailoring, and some eastern manufactured products. Church and Relief Society leaders dedicated the hall on August 5, 1869, only three months after the completion of the transcontinental railroad. It was no accident that the hall was built one block east of the Utah Central Railroad’s first depot, completed in early 1870, which linked the transcontinental line with Salt Lake City. Mormon women were asked to assist the church in countering the anticipated adverse moral and economic impact the railroad was to have on the city.

The west side Relief Society Store was the first of its kind for the church. Over the course of the following fifty years, 130 other Relief Society halls were built to meet the organizations expanding programs and interests. These halls were women-centered and women-controlled spaces, which were emblematic of a half-century of independent actions by and for LDS Church women. The intent of the Fifteenth Ward Relief Society store—along with other church-owned mercantile establishments, established in response to the growing political and economic power of non-Mormon and Mormon business interests—was to grow or manufacture goods that members could buy exclusively from merchants who were members of the LDS Church.

The Fifteenth Ward Relief Society Store and Hall served as a model of the LDS Church’s women’s industry and economic power. It also served as a key meeting place for community outreach. As a store, women found empowerment in establishing tailoring services, purchasing and using new mechanical sewing equipment, and building and managing an adjacent grain storage facility. Concurrently its second-floor hall was used by Mormon women’s suffrage leaders to gather, speak, and plan during the last quarter of the nineteenth century.

Women’s efforts to secure the right to vote in Utah were, to say the least, complex. On one hand, Utah had a large number of women who practiced polygamy and also engaged in independent social and economic practices. These pursuits included building and owning halls, selling home industry goods, building granaries, storing and owning large quantities of needed resources, and often meeting and planning both women’s and civic matters separately. The demands of polygamy life left wives working and living often as separate households, which developed a unique context for personal, family, and social independence; by no means rare but infrequent in nineteenth century America.

On the other hand, Utah had an equally strong contingency of non-Mormon women who also desired political equality. Nearly all of these non-Mormon women were Protestant, and some engaged in correspondence with national missionary organizations and with congressional leaders who expressed concern about Mormon women’s suffrage. Many national leaders feared that if Utah’s LDS Church-supported suffrage proved successful, female voters would contribute to an even stronger and more dominant Mormon society. Many Protestant leaders believed that the Mormon practice of polygamy threatened Christian values and American democracy. Thus, most Protestant women in Utah worked to resist Mormon women’s suffrage efforts.

Returning to economic matters, the LDS Church’s efforts to control the territory’s economy, including Mormon women’s mercantile efforts, largely failed as Utah experienced an industrial-urban transformation after the mid 1880s. Incoming non-Mormon and eventually Mormon capital on the wings of free enterprise, industry, and commerce, transformed Utah, Salt Lake City and especially the west side, which largely served as the center of this change, from an agricultural-based world to a post-Civil War industrialized world.

The arrival of the railroad and new industry brought laborers to Salt Lake City. The migration of so many people called for the construction of boarding houses, tenement houses, apartment buildings, and hotels. Additionally, many private homes were converted into boarding houses, offering room and board to renters. An extant example of a west side boarding house is the 1885 Victorian Italianate Lewis S. Hills House located at 126 South 200 West, just west of the Salt Palace. The building became the Hogar Hotel from 1928 into the 1970s after the prior owners, the Robert T. Burton family, sold the property. The Hogar Hotel provided a gathering place for Basque Americans who immigrated from Spain and France. They lived in Salt Lake City when they were in-between sheep herding and agricultural jobs throughout rural Utah, northern Nevada, and southern Idaho.

Salt Lake City’s earliest inns and boarding houses were located around Main Street near Temple Square. However, after the 1880s, the west side, with its numerous railroad depots and businesses, also amassed boarding houses, hotels, and tenements. Additionally, many new Main Street hotels constructed during the 1880s and 1890s were built on, or below, 300 South where non-Mormon or “Gentile” businesses had congregated. Thus by 1880, the Pioneer Park neighborhood was equally known for catering to non-Mormons and railroad tourists, as it was for housing laborers working in west side rail yards and depots.

From 1880 to the 1930s, downtown Salt Lake City – and most particularly the Pioneer Park neighborhood – was the home of nearly a hundred two- and three-story hotels with stair entrances on the side and ground floor retail spaces facing the street. Prior to the 1890s, boarding house residents or inns expected innkeepers to provide meals along with a bed or a separate room. After the mid-1880s, the “European Plan” came into vogue in Salt Lake City, offering different sized rooms and varying guest amenities. The new European Plan hotels did not include communal meals and offered less interactions with fellow guests. Many of these small hotels had restaurants or taverns where guests could purchase meals if wanted. Some later extant examples of European Plan hotels include the Rio Grande Hotel, located at 428 West 300 South, the Broadway Hotel located at 222 West 300 South, and the Peery Hotel located at 110 West 300 South. Each of these businesses attracted visitors from across the country and around the world to Salt Lake’s west side.

The Hotel Columbus opened in the Pioneer Park neighborhood at 252 West and South Temple. The family of Italian immigrant John Crus, who was born in Utah in 1910, owned and operated the hotel. The hotel was a small establishment with twelve rooms. It mainly housed unmarried Italian immigrants who appreciated the fact that an Italian family owned the hotel. The owners fed their guests a typical light Italian breakfast and made meals for working residents to pack in their lunch buckets. At that time, the majority of the Italian American tenants worked for the railroads or in mines or smelters. Later in his life, Crus recalled how his mother cared for young, recently immigrated, Italian laborers. He also remembered that his mother worked constantly and retired late in life. The immigrants, he remembered, felt that the Hotel Columbus made them feel at home in an otherwise foreign city. Dozens of small hotels on the west side catered to specific nationalities such as Hotel Columbus.

As you can see, as the nineteenth century drew to a close, Salt Lake’s west side offered a variety of housing, employment, and economic opportunities for immigrant laborers and visitors alike. Join us for our next installment in Salt Lake West Side Stories where we will discuss the development of the city’s warehouse district (you might guess most of Salt Lake City’s warehouses were and are located on the west side), followed by the story of the Liberty Bell, which was exhibited by train adjacent to Pioneer Park.

Do you want to read the next post (Post 11)? THE PIONEER PARK NEIGHBORHOOD’S WAREHOUSE DISTRICT AND A VISIT FROM THE LIBERTY BELL

Click here to return to the complete list of posts.

Related Activities: There were two anniversaries in 2020 significant to the history of Utah Women. The year 2020 marks the 150th anniversary of the Utah law that granted women the right to vote. Utah was second in the nation to extend the right to vote to women (1870) but first in the act of voting. Then, in 1920 (100th anniversary), the 19th Amendment was ratified, giving the vote to most women (sadly this did not include Native American women, nor Asian-born women or, because of Jim Crow laws, African American women). Listen to BetterDays 2020 historian Dr. Katherine Kitterman, speak about the key issues and dates related to the Utah suffrage movement in the Utah Department of Cultural & Community Engagement’s podcast Speak Your Piece: A Podcast About Utah’s History.

We urge that you also read “Gaining, Losing, and Winning Back the Vote: The Story of Utah Women’s Suffrage,” by Barbara Jones Brown, Naomi Watkins, and Katherine Kitterman from the website Utahwomenhistory.org.

Contributors: A special thanks to Dr. Katherine Kitterman, the History Director of History for BetterDays 2020 (at the time of this post), for consulting with the contents of this post. Thanks to historian Dr. Cassandra Clark for her observations and refinements.

This post was researched and written by Brad Westwood with a whole lot of help from friends. Thanks to our sound engineer and recording engineer Jason T. Powers, and to his supervisor Lisa Nelson, both at the Utah State Library’s Reading for the Blind program. Thanks also to yours truly, David Toranto, for narrating this post.

Selected Works:

Read the John Crus Oral Interview, in Leslie G. Kelen and Eileen Hallet Stone, Missing Stories: An Oral History of Ethnic and Minority Groups in Utah (Logan: Utah State University Press, 2002), 288-294.

Carolyn Butler-Palmer, “Building Autonomy: A History of the Fifteen Ward Hall of the Mormon’s Relief Society,” Buildings & Landscape: Journal of Vernacular Architectural Forum, Vol. 20, No. 1 (Spring 2013): 69-94.

Thrive125’s (Utah125th statehood anniversary) short film Becoming Utah: Women and the Quest for Political Representation.

T. Michael Hunter, “A Time for Change: Improving Salt Lake City, 1890-1925,” Pioneer (Autumn 2003): 18-24.

“Warehouse District (Salt Lake City),” Wikipedia, a U.S. National Register of Historic Places Historic District bounties: 200 South and Pierpont Ave. between 300 and 400 West, and roughly bounded by I-15, US 50 S., W. Temple St., 300 West & 1000 South.

Emmeline B. Wells, ed., Charities and Philanthropies. Woman’s Work in Utah, World’s Fair Edition, (Salt Lake City: George Q. Cannon & Sons Co., 1893).

Do you have a question or comment? Write us at “ask a historian” – [email protected]