Date: December 23, 2019 (Season 1, Episode 7 – Part 1: 25 min. & 3 sec. long and Part 2: 26 min. & 1 sec. long). Click here for Part 1 and Click here for Part 2 of the BuzzSprout versions of this Speak Your Piece two-part episode. The above cropped photograph is of Fort Douglas Cemetery (June 1963), one of the Utah cemeteries mentioned in this two-part episode. Photo courtesy of the Classified Photograph Collection, Utah State Historical Society. Are you interested in other episodes of Speak Your Piece? Click Here. This episode was co-produced by Brad Westwood and Chelsey Zamir, with help (sound engineering and post-production editing) from Conner Sorenson of Studio Underground.

This SYP episode is an interview with Amy Barry, the program manager for Utah Division of State History’s Utah Cemeteries and Burials Program, with SYP host Brad Westwood. At the time of this recording, Barry has managed the Utah Cemeteries and Burials Program for nearly 5 years and has always enjoyed spending time in cemeteries and is glad to have a professional reason to explore them more frequently. With a background in public administration, Barry enjoys using those skills to make government more accessible to everyone. The public can visit the Cemeteries and Burials Program online where they can search for a specific Utah burial plot by name, find a specific cemetery within the state, find out further information about Barry’s gravestone preservation program and efforts, and search for death certificates. The state of Utah is the only state mandated (since 1997) to collect burial information for cemeteries and import it into a searchable database, plus maintain a list of all cemeteries in Utah. As Barry puts it, her job will “never be done.”

Podcast Content:

Part One of Two:

Part Two of Two:

The Cemeteries and Burials database has an average of about 690,945 records (at the time of this recording in 2019). Since starting her position at the Utah Cemeteries and Burials Program, Barry has added about 90,000 records, but she emphasizes quality over content and prefers for the records to be as detailed as possible. She’s contributed to 49,000 already existing records to make them more complete. The database also includes about 621 cemeteries within the state. These cemeteries include individual burials, family cemeteries, and abandoned cemeteries as well. The database deals with municipal, private, federal, and one burial to thousands of burial plots. Additionally, many unknown burial plots have the help of one of Barry’s researchers in hopes of identification.

What makes this database a unique and different resource? Most cemetery or burial databases are often user-created while this database is based on independent research with government related resources plus Sexton Records (records kept by the sexton, or “caretaker” of a government, corporate, or church cemetery).

Every Monday, Barry posts on Utah State History’s Facebook page where she posts a biography of a person buried in Utah who has a compelling story and has contributed to their community. She specifically focuses on people who, very often, are people you may not know about or have heard of.

One specific story that Barry tells is of Joe Melich (born Novak Bogdanovich), born in Croatia in 1882. Melich immigrated to the US and made his way to Utah in 1904, when he settled in Bingham Canyon in a mining town. Melich became a well-known figure within the Serbian community in his town, where there was a small minority of Serbian immigrants due to the mining industry. Melich joined the Serbian army during WWI and was prominent in recruiting other Serbians to fight in the war. Although for the rest of his life he remained in Utah, he remained a prominent Serbian voice for the community. He later founded Phoenix, Utah (no longer in existence) and became mayor. He died in 1922 and is buried in the Bingham City Cemetery. Melich influenced the communities he lived in and had children that were also influential and participated in civic life in Utah.

Caption: Veterans Memorial located in Bingham City Cemetery (November 11, 2005) by Christina Epperson. Photo courtesy of Utah State Historical Society.

Barry concludes Part 1 of this episode by stating that although Utah’s interest in cemeteries is growing, with many undertaking well-meaning efforts of gravestone preservation themselves, this is often doing more harm than good. For this exact reason, Barry put together a gravestone preservation workshop as well as an instructional pamphlet and guide to clean and correctly preserve gravestones. She states her rules for preservation: 1. Do no harm, 2. Don’t do anything that can’t be undone!

The first story in Part 2 is of Sarah Elizabeth Nelson Anderson who was born in Kaysville in 1853. During this time, women were voting in elections at the time when Utah was a territory and hadn’t been granted statehood yet. However, with the Edmunds-Tucker Act 1887 many women lost the right to vote, leaving women out of national, state, and local elections. The Act didn’t spell out whether women were allowed to cast a vote in a territory not yet granted statehood yet, so Anderson, a vocal suffragist, decided to challenge this and cast a ballot in the Ogden 2nd Precinct where elections were being held to vote for Utah’s statehood. Her vote was denied, and Anderson filed a lawsuit which she unfortunately lost, but Anderson set the stage for the larger battle for women to gain the right to vote.

Caption: Sarah Elizabeth Nelson Anderson. Photograph courtesy of the Classified Photo Collection, 921 Biography; Utah State Historical Society.

The next story is of Lucy Augusta Rice Clark who was born in Farmington in 1850. Clark, a woman seemingly untirable, became a charter member of the Utah Women’s Press Club, an active participant in the women’s suffrage movement, served as president and vice-president of many different associations, and ran for office. The latter of which she unfortunately lost to a man who said he would have been so incredibly embarrassed had he lost the election (to a woman). While her participation in local politics at the time wasn’t seen as a positive thing, Clark was yet another woman who paved the way for women to come.

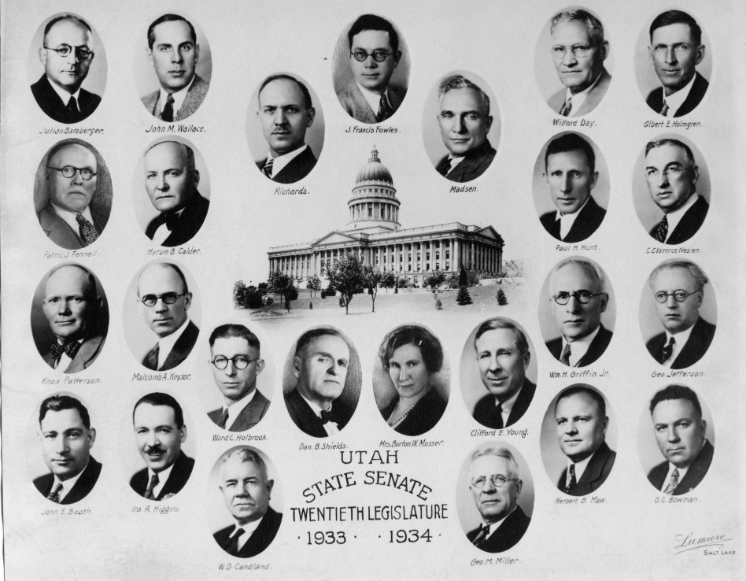

Elise Furer Musser is another woman mentioned by Barry. Musser, born in Switzerland in 1877, converted to Mormonism on her own as a young teen and immigrated to the US with “much hope and anticipation.” Upon arrival to the US, and Utah, Musser’s hopes were dashed as she had no one waiting for her at the train station and no clue where to go. A man who had been a mission president in Switzerland took her in and brought her with him to Mexico. Unbeknownst to Musser, however, the man was attempting to start a polygamist compound. She instead found work and saved up to return to Utah. She married, had children, audited classes at the University of Utah (women weren’t allowed to attend classes as official students), and gave much of her time to the Utah Red Cross. She became acquainted with the Neighborhood House – originally part of the Pioneer Park Neighborhood outlined in Salt Lake West Side Stories – where she was an interpreter for immigrants, taught English, and cared for children. She never stopped working at the Neighborhood House where she had an immense impact on her community. She ran for state senate in 1932 and won. Musser died in 1967.

Caption: Elise Furer Musser is the only woman depicted in the photograph (bottom center). Photograph courtesy of the Classified Photo Collection, 353 Government and Administration, State; Utah State Historical Society.

Barry’s final story in part 2 is one she originally told during the Fort Douglas Cemetery Tour in 2019 of Leopold Antone Yost, born in 1881 in Czechoslovakia. Jost immigrated to Iowa with his family in 1885. He later enlisted in the army in 1904 where he had a rich nearly 40-year long career. During his military career, Jost and his wife and kids were transferred to Fort Douglas in 1922. Jost, a self-taught trumpet player, became a band leader in the military and very popular among his peers and colleagues. He retired in 1945 and he and his family settled in Utah. He died in 1951 and is buried at Fort Douglas. Since he was such a well-loved figure in his community, the military allowed his daughter and wife to be buried alongside him, something which is uncommon in military burial plots but likely proves the status and influence he held within his community.

Barry concludes part 2 by stating that although many of these stories told are of immigrants, not originally from Utah, these people had a major impact in their communities. Whether it was fighting for and elevating women’s rights or playing in a band that brought a lot of spirit during wartime, these stories detail the otherwise unknown lives of people who contributed to our communities and whose influences live on. Stories which Barry attempts to encapsulate and immortalize within her detailed database.

Bio: Amy Barry is the program manager for Utah Division of State History’s Utah Cemeteries and Burials Program. Privately she serves as chair of the Sugar House Community Council (Salt Lake City, Utah). She has also chaired Salt Lake City’s Parks, Natural Lands, Trails and Urban Forestry Advisory Board, and was founder and former chair of Sugar House Farmers Market. She earned a BS degree in Geography from the University of Utah, an MS in Environmental Studies at the University of Montana, and a second MS in Political Science/Public Administration from the University of Utah.

Additional Resources & Readings:

- Cemeteries & Burials website: Cemeteries and Burials | Utah Division of State History.

Do you have a question or comment, or a proposed guest for “Speak Your Piece?” Write us at “ask a historian” – askahistorian@utah.gov